As part of my research I have been developing a Fortran source-to-source compiler — in Perl. The compiler transforms legacy FORTRAN 77 scientific code into more modern Fortran 95. For the reasons to target FORTRAN 77, please read my paper. The compiler is written in Perl because it is available on any Linux-like system and can be executed without the need for a build toolchain. The compiler has no external dependencies at all, so that it is very simple to install and run. This is crucial because my target users are weather and climate scientists, not programmers or computer scientists. Python would have been a viable alternative but I personally prefer Perl.

Perl performance as we know it

An often-made argument is that if you want performance, you should not write your code in Perl. And it is of course true that compiled code will almost always be faster. However, often rewriting in a compiled language is not an option, so it is important to know how to get the best possible performance in pure Perl. The Perl documentation has perlperf which offers good advice and these tips provide some more detail. But for my needs I did not find the answers there, nor anywhere else. So I created some simple test cases to find out. I used Perl version 5.28, the most recent one, but the results should be quite similar for earlier versions.

Testing some hunches

Before going into the details on the performance bottleneck in my compiler, here are some results of performance comparisons that influenced design decisions for the compiler. The compiler is written in a functional style — I am after all a Haskell programmer — but performance matters more than functional purity.

Hash key testing is faster than regexp matching

Fortran code essentially consists of a list of statements which can contain expressions, and the parser labels each of the statements once using a hashmap, ever the workhorse data structure in Perl. Every parsed line of code is stored as a pair with this hashmap (which I call $info):

my $parsed_line = [ $src_line, $info ];

This means than in principle I can choose to match a pattern in $line using a regex or use one of the lables in $info. So I tested the performance of hash key testing versus regexp matching, using some genuine FORTRAN 77 code:

my $str = lc('READ( 1, 2, ERR=8, END=9, IOSTAT=N ) X');

my $info={};

if ($str=~/read/) {

$info->{'ReadCall'}=1;

}

my $count=0;

for my $i (1..100_000_000) {

if ($str=~/read/) {

$count++;

}

for my $i (1..100_000_000) {

if (exists $info->{'ReadCall'}) {

$count+=$i;

}

}

Without the if-condidion, the loop takes 3.1 s on my laptop. The loop with the regexp match condition takes 10.1 s; with the hash key existence test it takes 5.6 s. So the actual condition evaluation takes 7 s for regexp and 2.5 s for hash key existence check. So testing hash keys is alsmost three times faster than simple regexp matching.

Custom tree traversals are faster

I tested the cost of using higher-order functions for tree traversal. Basically, this is the choice between a generic traversal which takes an arbitrary function that operates on the tree nodes:

sub _traverse_ast_with_action { (my $ast, my $acc, my $f) = @_;

if ( <cond> ) {

$acc=$f->($ast,$acc);

} else {

$acc=$f->($ast,$acc);

for my $idx (1 .. scalar @{$ast}-1) {

(my $entry, $acc) =

_traverse_ast_with_action($ast->[$idx],$acc, $f);

$ast->[$idx] = $entry;

}

}

return ($ast, $acc);

}

or a custom traversal:

sub _traverse_ast_custom { (my $ast, my $acc) = @_;

if ( <cond> ) {

$acc=< custom code acting on $ast and $acc>;

} else {

$acc=< custom code acting on $ast and $acc>;

for my $idx (1 .. scalar @{$ast}-1) {

(my $entry, $acc) =

_traverse_ast_custom($ast->[$idx],$acc);

$ast->[$idx] = $entry;

}

}

return ($ast, $acc);

}

For the case of the tree data structures in my compiler, the higher-order implementation takes twice as long as the custom traversal, so for performance this is not a good choice. Therefore I don’t use higher-order functions in the parser, but I do use them in the later refactoring passes.

Maps are slower than for-loops, but not much

Finally I tested the cost of using map instead of a foreach-loop:

# map, so much more concise!

my @src = map {$_} (1 .. 10_000_000);

my @res = map {2*$_+1} @src;

# declarations for all for-loops

my @res=();

my @src=();

# foreach-loop

for my $elt (1..10_000_000) {

push @src, $elt;

}

for my $elt (@src) {

push @res, 2*$elt+1;

}

# index-based for-loop

for my $idx (0..10_000_000-1) {

my $elt=$idx+1;

$src[$idx] = $elt;

}

for my $idx (0..10_000_000-1) {

my $elt=$src[$idx];

$res[$idx] = 2*$elt+1;

}

# C-style for-loop

for (my $idx=0;$idx<10_000_000;++$idx) {

my $elt=$idx+1;

$src[$idx] = $elt;

}

for (my $idx=0;$idx<10_000_000;++$idx) {

my $elt=$src[$idx];

$res[$idx] = 2*$elt+1;

}

The foreach-loop version takes 2.6 s, the map version 3.3 s, so the map is 25% slower. For reference, the index-based for-loop version takes 3.8 s and the C-style for-loop version 4.4 s — don’t do that!

Because the map is slower, again I did not use it in the parser, and I implemented my own higher-order functions which use foreach-loops internally for the refactoring passes.

Compiler bottleneck: expression parsing

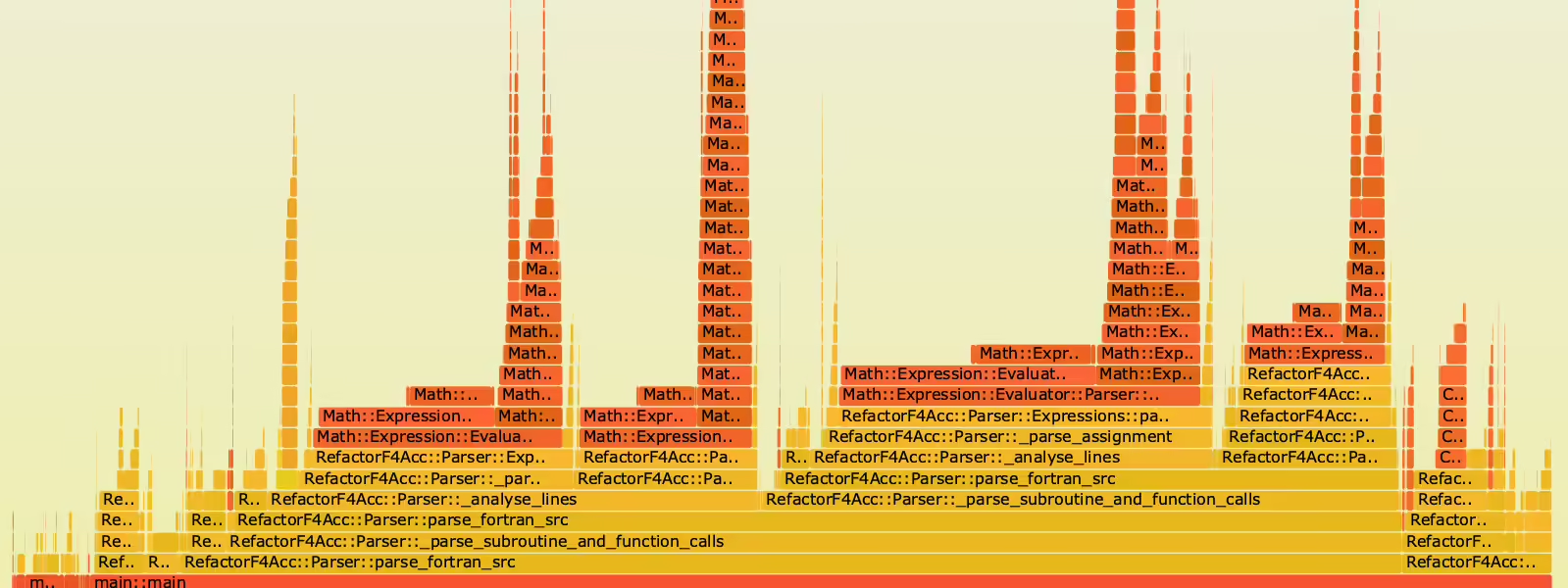

As the compiler grew in capabilities, it became noticeably slower. Perl has a great profiling tool, Devel::NYTProf, and I used it to identify the bottleneck. As you can see from the flame graph in the banner image, it turned out to be the expression parser. This part of the code was based on Math::Expression::Evaluator because it was convenient to reuse. But it was not built for performance, and also not to parse Fortran. So I finally bit the bullet and wrote my own.

What I loosely call an expression parser is actually a combination of a lexer and a parser: it turns a string of source code into a tree-like datastructure which expresses the structure of the expression and the purpose of its constituents. For example if the expression is 2*v+1, the result of the expression parser will be a data structure which identifies the top-level expression as a sum of a multplication with the integer constant 1, and the multiplication of an integer constant 2 with a variable v. So how do we build a fast expression parser? It is not my intention to go into the computing science details, but instead to discuss the choices to be considered.

Testing some more hunches

First, the choice of the data structure matters. As we need a tree-like ordered data structure, it would have to be either an object or a list. But objects in Perl are slow, so I use a nested list. As it happens, Math::Expression already uses nested lists. Using the parser from Math::Expression, the above expression would be turned into:

['+'

['*',

2,

['$','v']

],

1

]

Integer comparison is faster than string comparison

This data structure is fine if you don’t need to do a lot of work on it. However, because every node is labeled with a string, testing against the node type is a string comparison. I did a quick test:

my $count=0;

my $str = '*';

for my $i (1..100_000_000) {

if ($str eq '*') {

$count+=$i;

}

}

my $c=42;

for my $i (1..100_000_000) {

if ($c == 42) {

$count+=$i;

}

}

On my laptop, the version with string comparison takes 5.3 s, the integer comparison 4.6 s. Without the if-statement, the code takes 3.1 s. In other words, the actual if with string comparison takes 2.2 s, with integer comparison 1.5 s. So doing string comparisons is 50% slower than doing integer comparisons. Therefore my data structure uses integer labels. Also, I label the constants so that I can have different labels for string, integer and real constants, and because in this way all nodes are arrays. This avoids having to test if a node is an array or a scalar, which is a slow operation.

So the example becomes :

[ 3,

[ 5,

[ 29, '2' ],

[ 2, 'v' ]

],

[ 29, '1' ]

]

Less readable, but faster and easier to extend.

Regexes are faster than string comparisons

Then we have to decide how to parse the expression string. The traditional way to build an expression parser is using a Finite State Machine, consuming one character at a time (if needed with one or more characters look-ahead) and keeping track of the identified portion of the string. This is very fast in a language such as C but in Perl I was not too sure, because in Perl a character is actually a string of length one, so every test against a character is a string comparison. On the other hand, Perl has a famously efficient regular expression engine. So I created a little testbench to see which approach was faster:

my $str='This means we need a stack per type of operation and run until the end of the expression';

my @chrs = split('',$str);

for (1..10_000_000) {

my @words=();

my $word='';

while (@chrs) {

my $chr = shift @chrs;

if ($chr ne ' ') {

$word.=$chr;

} else {

push @words, $word;

$word='';

}

}

push @words, $word;

}

for (1..10_000_000) {

my @words=();

while(length( $str ) > 0) {

if( $str=~s/^(\w+)//) {

push @words, $1;

}

else {

$str=~s/^\s+//;

}

}

}

}

On my laptop, the FSM version takes 3.25 s, the regex version 1.45 s (mean over 10 runs), so the regexp version is twice as fast — the choice is clear.

A faster expression parser

With the choices of string parsing and data structure made, I focused on the structure of the overall algorithm. The basic approach is to loop through a number of states and in every state perform a specific action. This is very simple because we use regular expressions to identify tokens, so most of the state transitions are implicit:

my $prev_lev=0;

my $lev=0;

my @ast=();

my $op;

my $state=0;

while (length($str)>0) {

# Match unary prefix operations

# Match terms

# Add prefix operations if matched

# Match binary operators

# Append to the AST

}

The matching rules and operations are very simple (I use <pattern> and <integer> as placeholders for the actual values):

- prefix operations:

if ( $str=~s/^<pattern>// ) { $state=<integer>; } - terms:

if ( $str=~s/^(<pattern>)// ) { $expr_ast=[<integer>,$1]; } - operators:

$prev_lev=$lev; if ( $str=~s/^<pattern>// ) { $lev=<integer>; $op=<integer>; }

Operators have precedence and associativity, and Fortran requires twelve precedence levels. In the “Append to AST” state, the parser uses $lev and $prev_lev to work out how the previously matched $expr_ast and $op should be appended to the @ast array. The prefix operations are handled by setting a state which is checked after term matching. The actual code is a bit more complicated because we need to parse array index expressions and function calls as well. This is done recursively during term matching; if a function call has multiple arguments, the parser is put into a new $state.

So the end result is a minimally recursive parser, i.e. it only uses recursion when it is really necessary. This is because Perl is not efficient in doing recursive function calls (nor in fact for non-recursive ones).

There is a lot of repetition of the patterns for matching terms and operators because if I would instead abstract the <pattern> and <integer> values by e.g. storing them in an array, the array accesses would considerably reduce the performance. I do store the precedence levels in an array because there are so many of them that the logic for appending terms to the AST would otherwise become very hard to read and update.

Expression parser performance

I tested the new expression parser on a set of 50 different expressions taken from a weather simulation code. The old expression parser takes 45 s to run this test a thousand times; the new expression parser takes only 2 s. In other words, the new parser is more than twenty times faster than the old one.

It is also quite easy to maintain and adapt despite its minimal use of abstractions, and because it is Fortran-specific, the rest of the code has become a lot cleaner too. You can find the code in my GitHub repo.

Summary

Here is a summary of all optimisations I tested. The tests were run using Perl v5.28 on a MacBook Pro (late 2013), timings are averages over 5 runs and measured using time.

| Optimisation | Speed-up |

|---|---|

| Hash key testing is faster than regexp matching | 3× |

| Custom tree traversals are faster than generic ones | 2× |

foreach is faster than map |

1.3× |

foreach is faster than indexed for |

1.4× |

foreach is faster than C-style for |

1.7× |

| Integer comparison is faster than string comparison | 1.5× |

| Regexp matching is faster than successive string comparisons | 2.2× |